By Ronna Wineberg

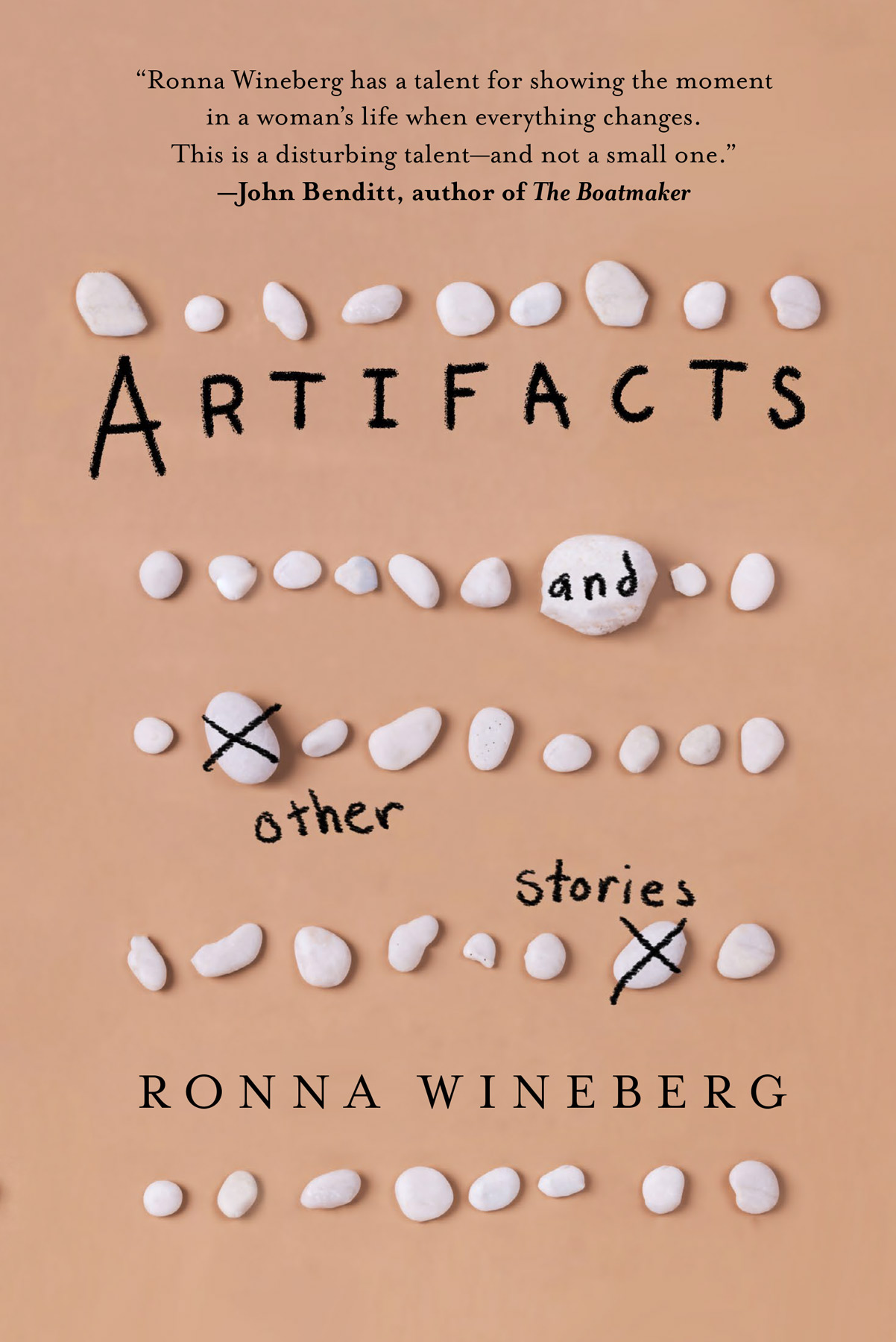

“Hurricane” is a short story from my new collection, Artifacts and Other Stories. The book will be published by Serving House Books. The fourteen stories explore the joys, limitations, and painful disappointments of love and attachment. “Hurricane” reflects these themes. It portrays desire, longing, marriage, adultery, aging, and the web of emotions that arise in the main character. The story looks at the sustainability of love and how a middle-aged couple with a daughter going off to college are navigating their lives.

In the collection, the characters wrestle with profound changes in their emotions and their closest relationships. Marriages are sustained or end, as secrets are kept or discovered, and as more is revealed, it becomes clear in every facet that the past lies just below the surface of the present. Friendship brings comfort, and love sometimes appears in unexpected places. The stories portray familiar relationships—between lovers, spouses, parents and children, and friends, and the often surprising choices we may find are at our doorstep.

When I was a child, I imagined life became steadier and more controllable when people were adults. But as I’ve grown older, looked at my life and the world around me, and written these stories, my perspective has shifted. That steadiness and control I imagined are illusions.

“Hurricane” first appeared in a slightly different form in Eureka Literary Magazine.

Hurricane

For weeks, Alice and her husband follow the paths of the hurricanes Ivan, Frances, and Jeanne. Every night, they sit side by side on the sofa in the den, a foot apart, and watch the television news, marveling at the wild, destructive powers of wind and weather. Now that Mara, their daughter and only child, has gone to college, she is not the main topic of conversation.

Will the storm touch Palm Beach or Fort Myers or Miami? Douglas wonders aloud. His mother used to live in Florida; they often visited there. How much damage will residual effects cause on the east coast or in New York City where they live? Alice nods, but she is not concerned with facts. Only with the photographs. Tears gather in her eyes when she sees footage of the newly homeless, smashed trailers, the guillotined trees. How can people live? Douglas talks about the force of the water, the longitudes and latitudes. He describes the historic nature of three storms emerging one after the other. She and Douglas are so skilled at discussing facts and probabilities about everything, Alice thinks, except themselves.

She doesn’t blame Douglas. Not completely. They live with silence, and she allows it. She doesn’t tell him this: her dissatisfactions with their marriage—though she has told him in the past—or about her lover, or her feeling, like a whirl of panic inside, that she is slipping farther and farther away, not just from Douglas, but from others, too. As if she has been shaken by uncontrollable forces—not unlike wind and weather—and although she is still intact, her insides feel hollow.

Ann Arbor, Michigan, where Alice grew up in the 1950s and ’60s, was a hotbed of strict morality. There were steadfast rules about how a girl should comport herself. When a boy and a girl are together, both the boy and girl should each have both feet on the floor. In a skirt, keep your thighs glued together. Wear blouses with Peter Pan collars buttoned securely. Alice silently reviews this litany as she sits next to Douglas. She had her short, sandy hair dyed this week, brushed with soft blonde highlights. She is slim and wears a low-cut black J. Crew sweater and jeans. Douglas stares at the television and doesn’t seem to notice her. Alice won medals in high school for diving and swimming. A way to control her bubbling teenage hormones, she thinks. She can still hear her mother’s voice: Never reveal cleavage or acknowledge you are endowed with breasts. Never display emotions, particularly desire.

“The world is falling apart,” Douglas says. “Terrorists. Iraq. Hurricanes. What next?”

He doesn’t seem to want an answer, and Alice nods again distractedly. She likes to imagine that her relationship with a man other than her husband is a mistake, as having happened against her will, as if she’d been dragged down to Hades by a force as strong as wind and fierce weather, to a den of iniquity and sexual pleasure.

*

Douglas enjoys traveling. He loves trips to obscure destinations and will never go on a tour. He teaches medieval history at a university, supervises graduate students, and writes scholarly papers; sometimes his travels are arranged for his work. He and Alice have visited ruins in all parts of the world. Machu Picchu, Sacsayhuaman, the Western Wall, Mesa Verde. Archeology was her favorite subject in college; it was Douglas’s, too. She is drawn to the fortitude of the ruins. She envies the stone. The strength, the silence, the absolute stability.

“Things were built solidly in ancient times,” Douglas said last year on a trip to Mexico. He likes to lecture and rattled off dates and dynasties. From the first, Alice loved his intellect and practicality, his ability to repair cars and electronics, to garden, jog, kayak. She didn’t realize how different they were: his efficiency and her delight in luxuriating in the world. His need to collect experiences as if they were treasured objects, and her need to talk to him about whatever thoughts or feelings flitted through their minds.

“You learn about a culture from their ruins,” he said as they walked past a stone pyramid. “About the way people live. What’s close to their hearts. Their souls.”

Alice listened carefully. Douglas usually didn’t talk about the soul. “I love these ruins, too,” she said.

“I can tell you’re thinking that I never talk about spiritual things,” he said and brushed a hand through his gray beard and mustache.

“You’re right. I like it when you do.”

“I do feel,” he said defensively. “I just don’t show it.”

*

It’s Monday, and during the workday, Alice listens to the radio to stay abreast of the news and follow the hurricanes’ paths. She checks her email for updates or messages from Mara. Hi, Mom. Doing fine. Where do I order contacts from again? College is GREAT. She misses Mara more than she anticipated.

Alice is a writer. She wasn’t always. She was a social worker first, and still is, a part-time social worker and part-time writer. This gives her the best of both worlds, she thinks, though she knows there are better ways to earn money. Three days a week at the Samuel Goldman YMCA on Fourteenth Street, she consults with private clients and runs groups for mothers of adolescent girls. She used to run groups for new mothers there, but she has decided that the challenges of a new mother, while they may seem profound at the time, are nothing like the angst of parenting an adolescent. A daughter’s constant critique and rejection can be deadly for one’s ego. This is what Alice tries to work on with her patients. Strengthening the mother’s ego. This is what you need in life, she believes, coping skills to guide you and others through whatever life brings.

Two days a week, she writes articles for a parenting magazine. “Articles” is an exaggeration; if she can write one piece or interview a few people, she is doing well. The writing, that process—the hammering out word by word, a sentence, a thought—takes longer than she ever imagined. But she’d always wanted to be a writer when she was a girl in Ann Arbor, swimming laps and struggling to cope with that strict moral code.

Writing complements her social work. She knows that with an adolescent, a mother needs to be direct, firm, and empathetic. No matter how difficult a daughter’s behavior. Just as one should be when writing or when talking with a spouse, though this is easier for Alice to do with her daughter than with Douglas.

Now that Mara is in college, Alice worries about sex and protection, emotional involvement and date rape, AIDS and STDs. On occasion, Mara has allowed her mother to discuss this. She has promised to insist a boy use a condom. To delay sleeping with someone until she is sure of emotional commitment, though Alice knows what a great request this can be.

Before Mara left for college last month, they had a talk.

“Even though we’ve discussed this before, I need to tell you again,” Alice said then.

“What?” Mara, tall and willowy, wore a gleaming gold stud in her nose. She tangled a long strand of her shiny brown hair around her finger.

Alice sat across from her daughter in the den and recited the litany. Like her mother had done when Alice was young. Delay sleeping with a boy until you are almost ready to marry. Alice stopped. “At least, until a relationship is serious,” she went on. Her mother had said until after you marry. She had referred to “relations,” not sex. And be faithful. Always.

Mara rolled her eyes. “Oh, Mom.”

Alice felt herself blush and inhaled a gulp of air. Did the scent of her lover still cling to her? Could Mara smell him? She smiled weakly at her daughter. Everything she has counseled Mara not to do, she does herself.

*

The relationship with Todd began in fantasy. Alice has high moral standards and a religious sensibility. She goes to synagogue because she enjoys the melodies, the feeling of being apart from the world, diving deep into herself and reflecting on God and prayer, gratitude and forgiveness. Douglas has no interest in this and works on Saturdays. He doesn’t believe in God. He says that synagogue and prayers are mumbo jumbo.

Todd attends synagogue, too. She noticed him four years ago and had imagined then how it might feel to make love to him. She was attracted to his wavy dark hair, his blue eyes and long lashes, wise eyes, she was sure, his trim body, the way he swayed in concentration in prayer. On some Saturdays, when both their spouses are otherwise occupied because neither spouse has a spiritual life, Todd and Alice meet at a hotel. They have done more things sexual together than she knew existed: top, bottom, side, anal, oral. A liberating litany of positions.

It is an odd ritual, Alice knows, after worshipping and imploring God for blessings, to then break a commandment. She no longer thinks of the commandments as carved in stone, though, of course, at one time they were. She thinks of them as floating commandments: if you are very good at following a few, perhaps it is not so terrible to break one. The truth floats, too. She is astounded by her ability to lie, to say she is going to synagogue when she is really meeting Todd. When she reads about adultery in the newspaper, the stoning of women or an article about a woman in Afghanistan imprisoned and sentenced to death for adultery, Alice feels both deeply ashamed of herself and thankful she was born a Jew. Douglas showed her an article last week and shook his head. “Not only do fanatics want to take over the world; they want to bring us to the moral dark ages. Not that adultery is to be condoned. But death?” Then he glanced at the green granite kitchen counter. “Can’t you throw out those newspapers? Go through the mail? Put away the groceries? The kitchen is a fucking wreck.”

“Cluttered,” she said. “Not a wreck. You don’t have to swear. It’s not the end of the world.”

Alice knows words are important. She has written about this in her articles. If a parent says to a daughter, “You make me sick when you stay out late,” the you make me sick lingers in the girl’s mind. Let’s say they are discussing curfew. The conversation becomes heated. The mother loses her temper. You make me sick. Those four words may be the only ones that remain in the daughter’s consciousness.

Words have become a problem for Douglas. “You are disorganized,” he says if Alice leaves dishes in the sink. “You can’t function,” he yells if she loses her keys. A social work friend once told her that at fifty-five, men become mean. That’s what happened with Douglas. It happened when he was younger.

Alice considers her time in the hotel with Todd an extension of her spiritual life. She has begun to view sex as spiritual. Because she feels so alive with him.

*

From the first, Alice noticed how Todd used words. The precision. He is a furrier and works in a small family business. Recently he has become interested in spiritual matters and studying Kabbalah. He was an English major in college, reads poetry and novels. He’s had thoughts about learning to become a healer. If it is possible for one person to heal another, he said. He was sure that phenomena existed in this world that one could not explain. “Take this, the two of us, sitting here.” They were at a restaurant.

She noticed how he spoke about fur, the gradations, the quality, the nap, cut of fabric. How he spoke about his family. His wife and two children, all of whom he loved. “I want to be clear from the start. I love them all.” He spoke about noticing Alice in the synagogue and the green of her eyes, he said, which were flecked with delicate gold.

*

On Saturday, in two days, Alice will meet Todd in a hotel. They always split the cost. He finds the place, using Priceline.com so they can get a deal. They have made love in large rooms with views of bridges, and rooms so small there is hardly space for a bed.

She became involved with him at the time Douglas’s father became ill. Douglas is an only child. His father moved in with them three years ago, six months before he died. Alice had underestimated the needs of the sick. She had been close to her father-in-law. The first week at their house, Harry developed violent diarrhea. He looked like a corpse. One morning at breakfast, he fell asleep at the table and began to lean to the left, almost slipping off the chair, and Alice ran to him. The man began to twitch as if his body were plugged into an electric socket. She yelled his name over and over until he finally replied weakly.

Alice prayed for God to give her the strength to handle the situation. That week she went to bed with Todd.

*

On Thursday night, the week of Hurricane Jeanne’s fury, Douglas walks out of the bathroom naked. Not without clothing, but without his beard and mustache. He has had these since Alice met him. She stares at him. He looks like a stranger. Even his smile is different. Wider. Unfamiliar.

“Do you like it?” he asks.

“I don’t know.” His chin is bare, without a cleft that she had imagined. The space between his nose and lips is smaller, his lips narrower. His mustache and beard were pepper-colored and set off his skin nicely. Now he looks sallow. Still, more youthful. But a stranger.

“Why did you do it?” she asks.

“I had gotten so gray. White even. I looked like an old man.”

“I didn’t think so. You should have asked me.”

“I didn’t think to.” He rubbed a hand against his bare chin. “Do you like it?” he repeats.

“We should talk about things. But yes, I like it.”

“Good. I was hoping you would. Just in time to surprise Mara.”

*

The next day, Mara comes home from college, her first visit, to see her parents and friends. Alice is struck by the glint of joy in Mara’s eyes as she sweeps into the apartment and plops down a duffel bag bulging with dirty laundry. She talks excitedly, nonstop, about the dorm, her roommate, classes. Douglas comes home early, and Mara tells them both about her favorite course, “The Uses of Enchantment,” named after a book by Bruno Bettelheim, she announces. “Do you know the difference between a myth and fairy tale?” she asks her mother.

Alice guesses. “Fairy tales tell stories, and myths have greater insights?” They sit side by side on the sofa, Alice’s arm around Mara.

Douglas looks on, sitting across from them.

“Close, but no cigar,” laughs Mara. “A myth is pessimistic, a fairy tale optimistic.”

“Like Persephone,” says Alice. “That’s a pessimistic story.”

“Yes,” agrees Mara. “Or Oedipus. It’s about fate. You can’t escape your fate in myths. The gods exact punishment. Myth is about superego.”

“To be Freudian,” says Douglas.

“Absolutely Freudian,” Alice says.

Mara chatters on. “Think of any fairy tale, like Hansel and Gretel. They got what they wanted. They escaped. And the names are generic, Little Red Riding Hood, the dwarfs, no character development.”

Like the husband, the wife, the lover, Alice thinks.

Douglas goes back to reading The New Yorker.

“Interesting,” says Alice. “That’s true. In fairy tales, you don’t know the characters like you know the gods. But novels really define character. Like Henry James’s novels. Virginia Woolf’s.”

“We aren’t reading them, Mom. That’s a class for next semester.” She stares at Douglas. “Dad, you shaved your beard and mustache. It looks good.”

He glances up from The New Yorker and smiles.

Before dinner, Douglas and Mara watch the news. Alice goes to her computer in the small room behind the kitchen while the lasagna bakes. Restlessness rises inside her just as it did when she began with Todd. Now she types: How to be a caretaker. She is writing an article about this. She thinks of all those for whom she has cared: her parents, her husband, daughter, father-in-law, her patients. And she would like to care for Todd. But he won’t let her. He has a wife. She types: You hold your breath when you begin a project because you could be interrupted any time. This small room has a high ceiling, its only asset, and one large window opens to a courtyard, but the window is painted shut. Alice stares outside. There is so much white, white like a dream, a cloud, a mist that obscures all vision. She hides here, waiting for tomorrow. She remembers the sounds of the bell when her father-in-law was too weak to speak; he shook a small glass bell to let her know he needed help.

She daydreams of Todd. He sings sometimes when they have walked along the East River, “Non, je ne regrette rien,” or the Beatles, “Yesterday, all my troubles seemed so far away.”He has brought the A-O volume of the Compact Edition of the Oxford English Dictionary to the hotel, and they have looked up words and discussed definitions and origins. She has dived into the muddy waters of emotion with him, has told him things she has never told anyone. He has confided in her. And he loves to garden. He has a small yard and a large townhouse, but would rather have a large yard and small house.

*

On Saturday, Alice goes to the service at the synagogue and afterward, in drizzle and dampness, to a hotel. Mara has made plans to spend the day with friends, and Douglas is working.

In bed, Alice traces Todd’s face with her hand. She loves his humanness, that the space between his nose and lips is not symmetrical, that his skin is creased by his smile, his body muscular, except when he stands and zips his jeans. The flesh is pliable by his waist.

“I love it when I see you,” she says.

“See me?”

“You know what I mean.” She laughs. “Like this.” She sweeps her hand across his chest and gazes at all the places she was taught not to look: chest, waist, genitals, the smooth curve of the thigh, and into his eyes. How much joy are you entitled to in life? she wonders. “When I see you, like this,” she says, “and then when you’re gone, I miss you all over again.”

“I miss you. That’s the nature of this kind of arrangement.”

She bites her lip. She hates when he mentions an arrangement. It makes what they do together seem transactional, without connection. Without feeling.

“I have less time than I thought today,” he says. “I’m sorry. My in-laws…” His voice trails, and she kisses him, muffling his words.

“I love you,” she says after they make love. She pulls the blanket over them to be sure he is warm.

He stares at the ceiling. He doesn’t need to speak. Alice can see the words forming in his thoughts. He loves the sex.

“Don’t say that,” he says. “I am very, very—”

She presses her hand to his lips. “Shh. Don’t say anything. It will ruin this.” They lie in silence, and after a few minutes, she slips out of bed and puts on her clothes. He watches, as he watched her undress. She doesn’t bother to shower. His salty scent clings to her like glue.

“You’re leaving?” he says. “Don’t. I still have time. I’ll leave just a little earlier than usual. Don’t go.”

He has told her this before. But she wants to leave first. It is too difficult when he is gone, and she is in a room alone. She blows him a kiss and smiles as she opens the door. “I’ll see you next time.”

*

Outside, the sky has darkened. Alice wanders from the hotel as the rain begins to trickle down. She thinks of all the ruins she and Douglas have visited. Ruined lives, hopes, plans. How the stones still stand despite wear and weather and neglect. She has always wanted to live happily ever after with Douglas. Now she doesn’t know how to live happily anymore.

She thinks of the phrase Todd mouthed once when she told him about her moral standards from childhood and that this made it difficult for her to have an affair. But not impossible. Hebrew words: Gam ze ya’avor. This too will pass, he said. She thinks of her expectations of him, her great need for him, of Todd’s lesser need for her. She remembers the ancient Hebrew prayer that people centuries ago wore in amulets around their neck: May the Lord bless you and keep you; may the Lord cause His face to shine upon you and be gracious unto you; may the Lord lift up his countenance upon you and grant you peace. And of the light in Mara’s eyes, her whole life ahead of her.

Guidance. Everyone is asking for guidance among the ruins.

She is not far from the Museum of Natural History and pops open her umbrella and hurries there in the dampness for shelter, past the dinosaurs that rise like bony giants to the gift shop. She buys rocks, all sizes, shapes, and colors, and pays with a credit card.

“These are heavy,” the saleslady says.

“I’ll put them in here.” Alice holds up the black canvas bag she got for free from Bloomingdale’s, shaped like one of the fancy French Longchamp bags Mara likes so much. “I’m not going far.”

Outside, the wind has picked up, and water lashes against her raincoat. The hurricane has trickled here, she thinks. She hops on a crosstown bus, and on Second Avenue, she manages to find a cab. She asks the driver to take her home, but then she changes her mind and asks to go to Eighty-Third Street, near the East River, near her favorite place on the promenade where she used to stroll with Mara when Mara was a child, where Alice first kissed Todd.

She imagines the stones she and Douglas have seen, how she admired them because of their sturdy silence. What have they witnessed? The weight of life. Births, deaths, misunderstandings. Wars and betrayals. They have survived them all. She remembers the thin white mist at Machu Picchu, on their honeymoon, mist so fine and delicate like a bride’s veil.

She has read books, stories, and clinical material about what it feels like to be the “other woman” and has discussed this with patients on occasion, but right now she would say this: the phrase describes the feeling completely. Other. Outcast. Pariah. Standing on the edge of a community. A hope. A shared life.

*

At the promenade, she walks in the rain. Not many people brave the elements, though she notices a few people yards away. She walks, bag of rocks in one hand, black umbrella in the other. The wind by the river is strong. Her sturdy umbrella has not been blown inside out yet.

She passes the spot where she and Todd first kissed, in the daylight, in the sunshine, kissed recklessly—what if someone they knew saw them? She didn’t care then. Todd liked the danger, and all she wanted was to touch his lips with hers, touch him, skin to skin. The most essential need that day by the river. She didn’t care what destruction this would bring. She would have given everything to touch him then, and she realizes that, in a way, she has. This is his cost to her. She has given up her peace of mind, integrity, her belief in goodness and morals, right and wrong. In all she was taught in Ann Arbor, Michigan. All she has tried to teach Mara. She has traded it for this: shades of gray. Ambiguity. Isolation. Patients who look to her for answers. A husband who reads instead of talking to her. A lover who has only small slices of time to give her. She has willed herself not to care about the contradictions in her life, but she is not stone.

She strolls past others who brave the weather. A heavy, sullen teenaged boy who wears a drenched white shirt; a red-and-blue baseball cap sits on his head backward. An old, bent woman with gray hair, who hobbles with a cane and wears a long brown raincoat and black orthopedic shoes, clumsy as boats. They are everywhere in New York, Alice thinks, people like this, the lost, the misplaced, the oddities, the forgotten, and although she knows she does not appear this way, with her pretend French bag and her chic khaki raincoat, an Eddie Bauer umbrella opened gracefully above her, inside she feels the same as she imagines these people must feel.

At her favorite spot along the East River, Alice stops. The wind blows fiercely and rain pours down. The residuals from the hurricane. If Douglas were here, he might comment on the speed of the wind, the amount of rain that falls per minute, and insist they seek shelter. These details are superfluous. It is simply not fit weather for man or beast. But she gladly lets the wind race through her hair.

The metal railing is slippery but she grasps hold of it, then, on a whim, climbs up onto the low cement wall. The rocks feel heavy in her bag. She wonders if someone will stop her, but this is New York. No one does. She stares at the horizon, far away, the expanse of Queens hazy in the rain, and she feels an odd liberation, so drenched she may never warm up.

She thinks about when Douglas’s father was dying with the chemo, and of her own mother in Ann Arbor, and all those beliefs her mother passed on like edicts. Then Alice imagines that she jumps, like she used to leap into the water as a child, falling down, down, unafraid—as if she is a character in a fairy tale or the puppet of a god in a myth, light and lithe as a girl, or as if she is Virginia Woolf herself—splashing into the murky, unforgiving water, shoes tumbling off, going to a place deep inside herself, leaving her confusion behind.

The wind whips against her. She blinks, gulps a breath. She throws a stone into the water, and another. Then she carefully climbs down the cement wall and stands in the fierce weather. She will give Mara these stones, artifacts of the earth’s history. She will give Douglas some, too, she decides, a gift, a kind of offering. She has nothing to really offer him, to offer herself. What can she give? Wavering affection, but affection nonetheless. Alice wishes she were made of stone, but she knows she is not. She turns away from the river. She imagines Mara and Douglas waiting for her, and she begins her journey home.

Ronna Wineberg is the author of Nine Facts That Can Change Your Life, a collection of short stories, which received Honorable Mention for the Eric Hoffer Book Award; On Bittersweet Place, a novel, winner of the Shelf Unbound Best Indie Book Competition; and a debut collection of stories, Second Language, winner of the New Rivers Press Many Voices Project Literary Competition, and the runner-up for the Reform Judaism Prize for Jewish Fiction. Her stories have appeared in Michigan Quarterly Review, North Dakota Quarterly, Colorado Review, American Way, and other literary journals, and have been broadcast on NPR. She was awarded a fellowship in fiction from the New York Foundation for the Arts, a scholarship in fiction to the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, and residencies to The Ragdale Foundation and the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts. She is the founding fiction editor of the Bellevue Literary Review and lives in New York.